A brass instrument can be a huge investment, so owners definitely want to keep them in tip-top shape. We hear from customers who are worried about a strange spot on their instrument. What caused it? Will it affect their sound? Will it continue to grow? Should they get it fixed?

This photographic guide should hopefully reassure you that your instrument is fine.

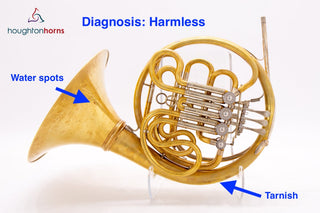

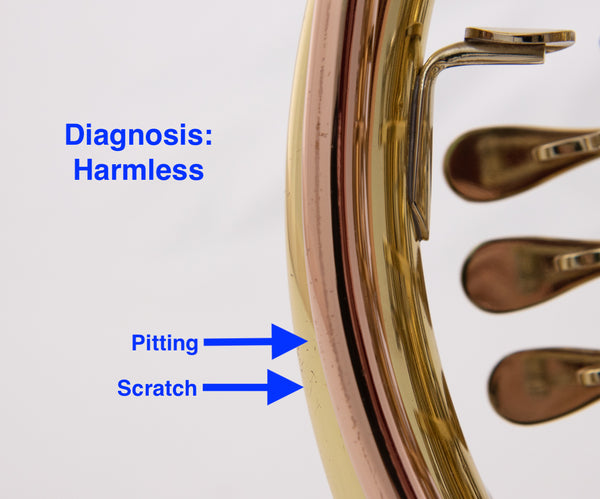

There are multiple scratches along this horn. A scratch in the lacquer on an instrument is nothing to be concerned about, and scratches can happen after only a few weeks of use. If the lacquer gets beat up enough, you might want to consider having the instrument re-lacquered or de-lacquered, just for appearance’s sake. Lacquer is a thin natural resin (nitrocellulose) or polymer coating that applied the body of an instrument. The player might notice that their instrument sounds different after removing the lacquer, but the difference will be nearly imperceptible to the average listener.

There may also be tiny little pits or dots in the lacquer. This might happen if bits of foreign matter such as dust got trapped when the lacquer was applied. It’s only a cosmetic issue and won’t affect the acoustic functioning of your instrument.

Unlacquered brass will start to tarnish immediately. You may notice after a couple of days that your hands are leaving reddish-brown prints in the horn. Over a period of time (weeks or months, depending on body chemistry), the brass will develop a brown patina. There is no way to stop the oxidation process, but it will not have any adverse effect on your instrument. Most professionals prefer the patina look anyway. By the way, the patina is a micro-thin “oxide coating” from the copper and other metals interacting with the atmosphere; the oxide layer actually protects the metal from the environment!

It’s okay to get your brass instrument wet. In fact, it’s recommended you take your horn apart and give it a bath every couple of months. A few drops of water on the surface may leave a mineral stain, but they won’t hurt your instrument at all. But if at all possible, completely dry out your instrument every time it’s exposed to water. Tap water has minerals and human saliva has food particles and alkalis that can build up inside your instrument. Over time they will need to be removed chemically or with an ultrasonic cleaning.

The dark spot on this horn is from a soldering torch that burned the lacquer when that brace was being repaired. It’s purely cosmetic damage and doesn’t affect the instrument.

“Acid bleeds” sometimes occur at points where the instrument is soldered together. We occasionally see this at the bell rim, or on a bell with a garland. The acid in the solder flux can seep into cracks or voids, and when the lacquer is cured (at around 300 degrees), it can bleed back out, staining the brass and remaining trapped under the lacquer. Acid bleeds only affect the appearance, and have no impact on the sound or longevity of your instrument.

Small, easily accessible dents are easy for a qualified repair technician to remove. (Don’t try to fix them at home!) If you show them to your repair tech they can probably roll them out in just a few minutes. Houghton Horns’ repair shop removes small dents like this for free included with any ultrasonic cleaning.

The larger the dent, or the closer it is to the mouthpiece end of the horn, the more it may have an impact on your sound, so you’ll want to get those taken care of.

One little dent or two isn’t a big deal. We’ve taken care of school band tubas that still sound great despite having been tossed around and repaired repeatedly for 10 or more years. Even so, try not to make a habit of damaging your instrument! Each time a dent is removed, it makes the metal in that spot less flexible and more brittle. This “work hardening” is characteristic of brass and other copper alloys.

PLEASE: Do your best to protect your horn! Knocking the horn around adds stress to the braces and tubing; every time your horn suffers an impact, it adds more stress. This stress and misalignment will prevent your horn from resonating like it should.

Here’s the spot no one wants to see: red rot.

“Red rot” occurs when the brass loses its zinc content. It has multiple causes: perhaps the instrument was made from a bad batch of brass, or the metal was overheated during construction, or the player’s personal body chemistry is interacting and leaching the zinc from the copper/zinc alloy.

It can happen to any horn, no matter how expensive. The more zinc in a brass alloy, the more likely red rot is to occur. Yellow brass is approximately 70% copper and 30% zinc, and is the most prone to this “de-zincification”. Gold brass (about 82% copper / 18% zinc), red brass (87% copper / 13% zinc), and nickel silver (70% copper / 10% nickel / 20% zinc) are much more resistant to this leaching. Red rot scares musicians because it slowly spreads through your instrument. As the zinc leaches out, the copper will be left behind, so the metal will turn a soft pink-brown-red in small spots. The metal at that point will be brittle and easily develop holes. Even if the red rot is shallow, it can eventually spread deep enough to weaken the metal to the point that an ultrasonic cleaning opens a hole.

Your mouthpipe is the spot most prone to red rot: this is where the food particles tend to collect, and where most of the chemical reactions are concentrated. Other parts of your horn – tuning crooks and small branches – can also experience red rot. Red spots in the bell tail or bell flare are not likely “red rot”, and shouldn’t be a cause for concern.

What you can do yourself:

The best way to protect your instrument from red rot is to be consistent about annual ultrasonic cleanings.

Consistent lubrication – including regularly dropping valve oil down your mouthpipe to provide a chemical barrier from grime & particles.

Regular snaking and rinsing the mouthpipe are also great preventatives. Why not make every first Sunday your horn maintenance day?

If you happen to have the type of body chemistry that interacts strongly with the brass in your instrument, you can use a hand guard to reduce the amount of time your skin spends directly in contact with the metal.

Once your horn develops red rot, there is nothing you can do to heal it. A repair technician can install a patch, but – in the case of severe wear – they might just have to replace an entire lead pipe, crook or slide tube. In an emergency, a small hole in your instrument can be sealed over with clear nail polish or even vinyl tape until a repair shop can permanently patch it.

All of this sounds ominous, but DON’T PANIC! Red rot spreads very slowly, so your instrument might have 5, 10, or 15 more years before it becomes a serious issue. Show the red spots to your repair technician at your next annual cleaning. If the instrument is very expensive or valuable to you, they may recommend a patch or replacement part. If it’s a less costly instrument and you’d be happy to get another good 5 years out of it, they might just recommend you ignore it. Young students can learn to play just fine on a horn with a little red rot, as long as there aren’t any actual holes in the tubing.

Minor red rot on a 35-year-old instrument.

Extensive red rot on a 40-year-old instrument. It was still being used in a school band program until we recommended retirement.

I hope this article is reassuring. In summary: if you see a spot, it’s probably not red rot, and even if it is, you’re probably okay for at least the next 5 years anyway. Just be diligent about cleaning your instrument according to the manufacturer’s recommended daily, weekly, monthly, and annual maintenance schedule.

Speaking of which…